How to monitor nearby bluetooth devices with a single command

Aspaldiko! It’s been a long time since I’ve been around here, it’s been a busy few months (work, moving house, Christmas,… a thousand things), but it was about time I got back to blogging a bit. Although I still have to continue the series on malware analysis, I’ve decided that, in the meantime, I’m going to post a few posts about some things I’ve been tinkering with lately, like this one, about monitoring bluetooth devices.

I love Linux. With linux terminal you feel powerful. It’s not that I’m an expert using it, but when you know your way around it, you can do a lot of things.

The other day I wanted to make a small script to monitor the bluetooth devices I have around me. I saw it as an interesting exercise to get data like how many devices I have around, see what kind of devices they are, how many devices are coming and going, and see what can be done with that information.

My instinct when I wanted to do something like that is to make a script (damn programmers, always reinventing the wheel). The scripting language I’m most comfortable with is Python, so I thought I’d use it to do this. Then I figured that what I really wanted to do was just use the output of a command (bluetoothctl), do four things and dump it into a file.

Then I thought that, for that, what I should do is more like a shell script than using something as overkill as Python. That way, I could use it all the time, less dependencies, etc.

I wondered if a script was really necessary for this. Maybe between pipes, greps and transformations I could make an oneline that I could put in an alias and that’s it. Sometimes, when I look for how to get certain info or how to do certain tasks in Linux, the results of sites like Super User show people putting crazy commands to do all kinds of things, so I thought I could do the same, or at least try to do it. So today I’m going to explain how to set up a command to monitor the bluetooth devices around me.

First things first. The bluetooth tool I used is bluetoothctl.

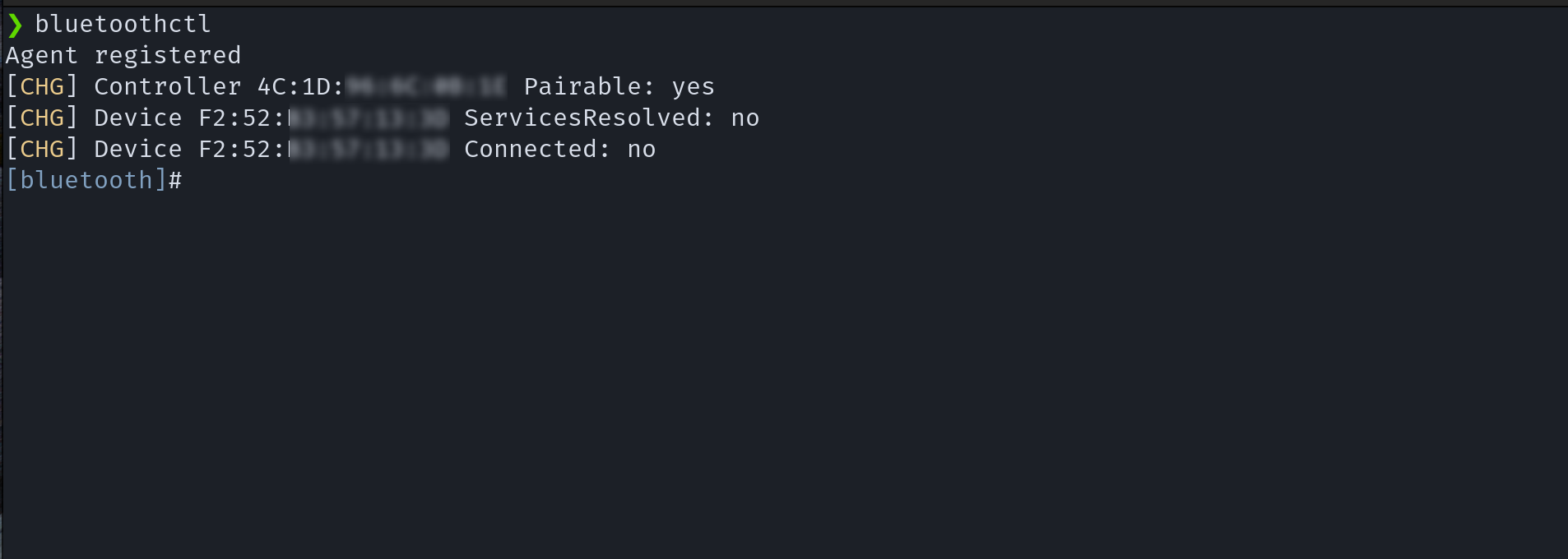

bluetoothctl

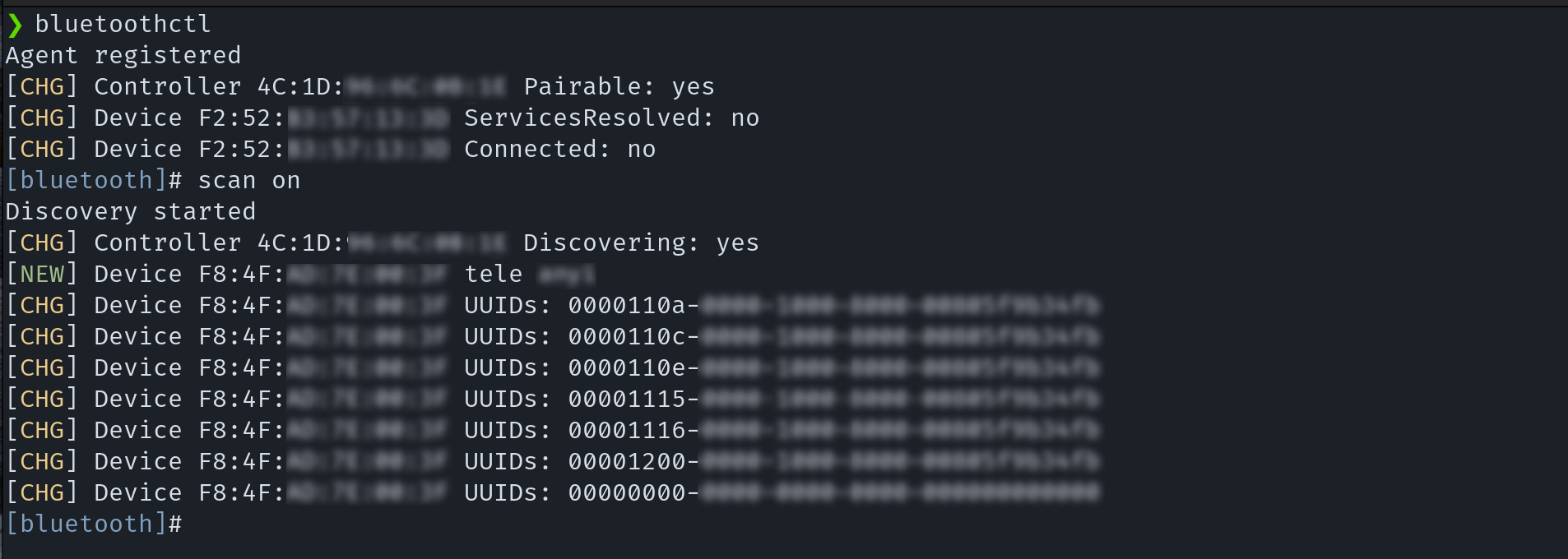

If run, it can be seen that it works in interactive mode. To scan for devices, you simply use the scan on subcommand, and it starts detecting devices that appear, disappear or change properties.

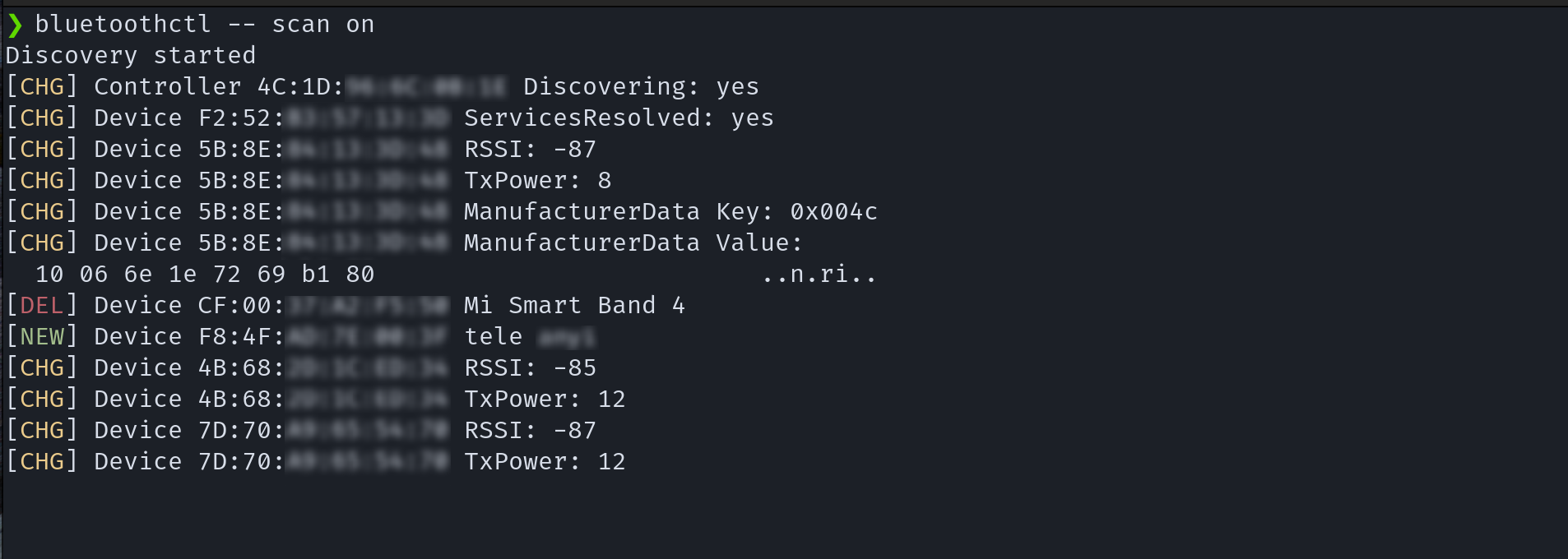

Here comes the first problem. Since I want to redirect the output of this, interactive mode doesn’t work for me. In Bash (and other shells like Zsh, which I use), a -- indicates the end of commands, after which you can pass parameters. So, if you put the following:

bluetoothctl -- scan on

It already returns everything via standard output and without interactive mode.

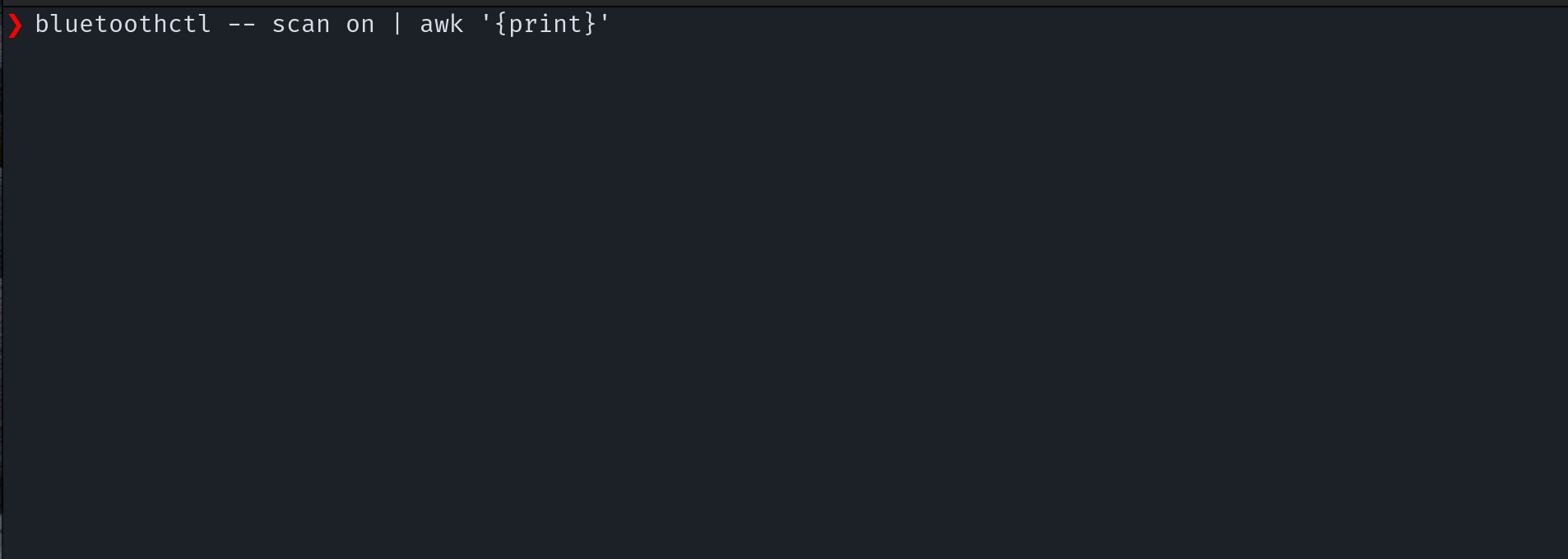

The next step is to start doing some transformations. First of all, I want to cut some parameters, dump this and filter some lines according to their content. For this I know that the best way is to use the advanced but intimidating awk. I have seen some videos about it but I have never used it beyond copy-pasting. Just to test it, I’ve tried using the option to print what it returns, as follows.

bluetoothctl -- scan on | awk '{print}'

Shit. Another problem. Nothing comes out. Looking on the internet, I see that the reason is a buffering issue. As the output is continuous, until the bluetoothctl buffer is freed, the output is not redirected to awk, so it is useless. Also looking on the internet, I see that I can solve this with stdbuf and some specific arguments.

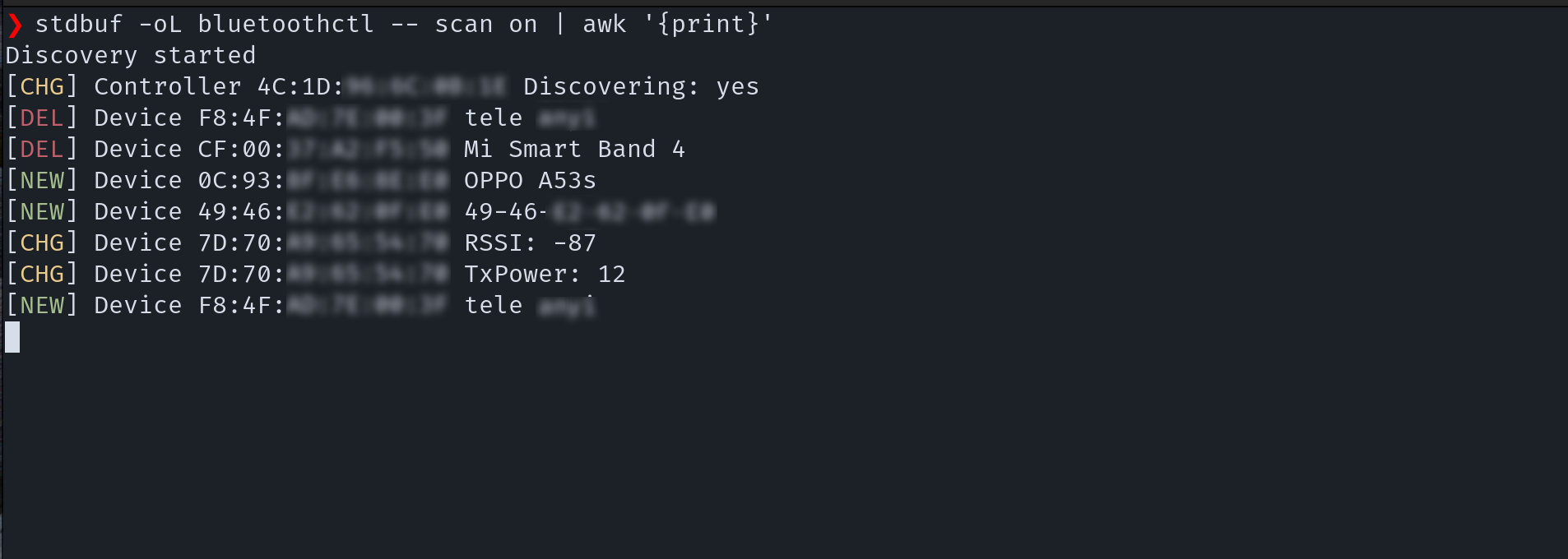

stdbuf -oL bluetoothctl -- scan on | awk '{print}'

(I will not go into the detailed explanation of all the commands and arguments, as I will never be able to do it as well as man or other anonymous internet users).

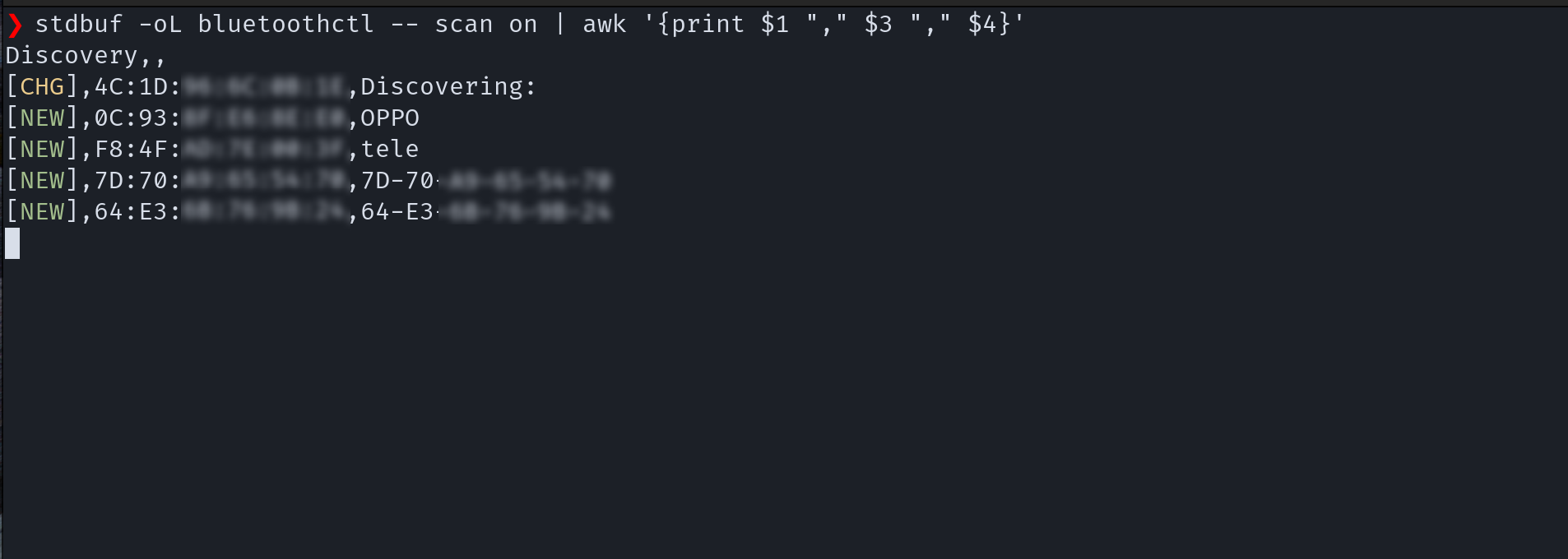

OK, now it works, so we can get serious. To show only certain parts, you can use the dollar syntax, which allows you to select certain parameters on each input line.

stdbuf -oL bluetoothctl -- scan on \

| awk '{print $1 "," $3 "," $4}'

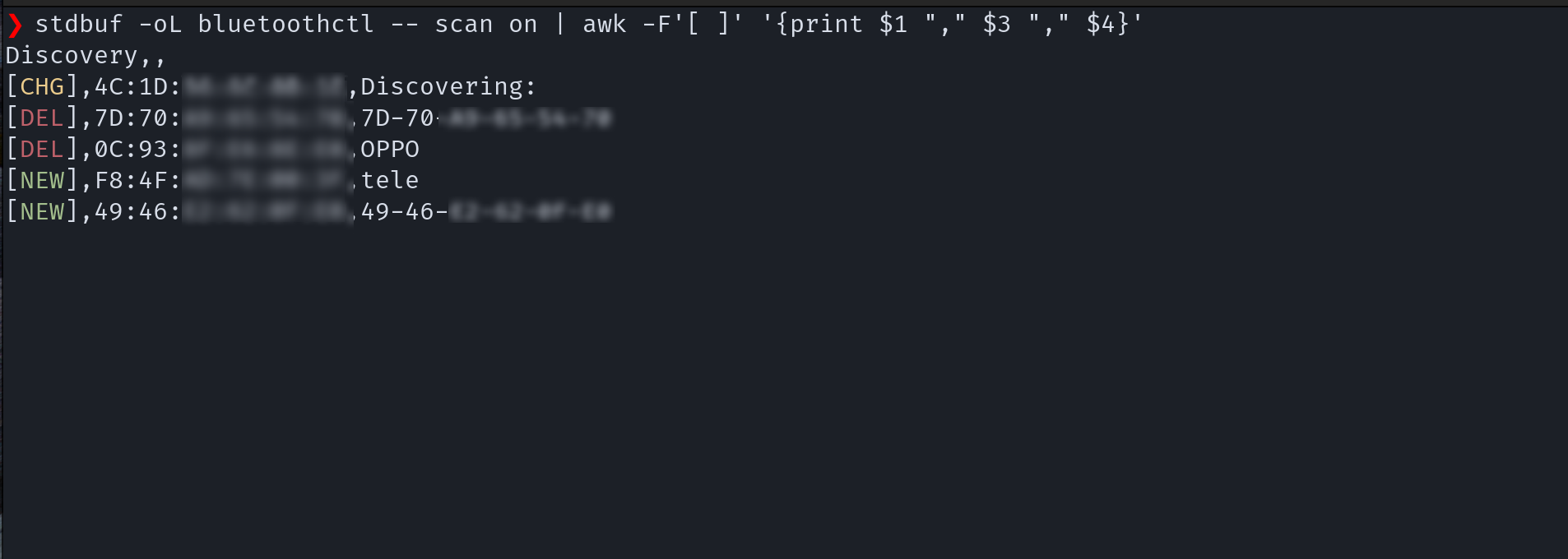

By selecting the first, third and fourth, only those fields are displayed. By default, the separator is the space, but if you want to specify or use any other separator, you can indicate it with -F.

stdbuf -oL bluetoothctl -- scan on \

| awk -F'[ ]' '{print $1 "," $3 "," $4}'

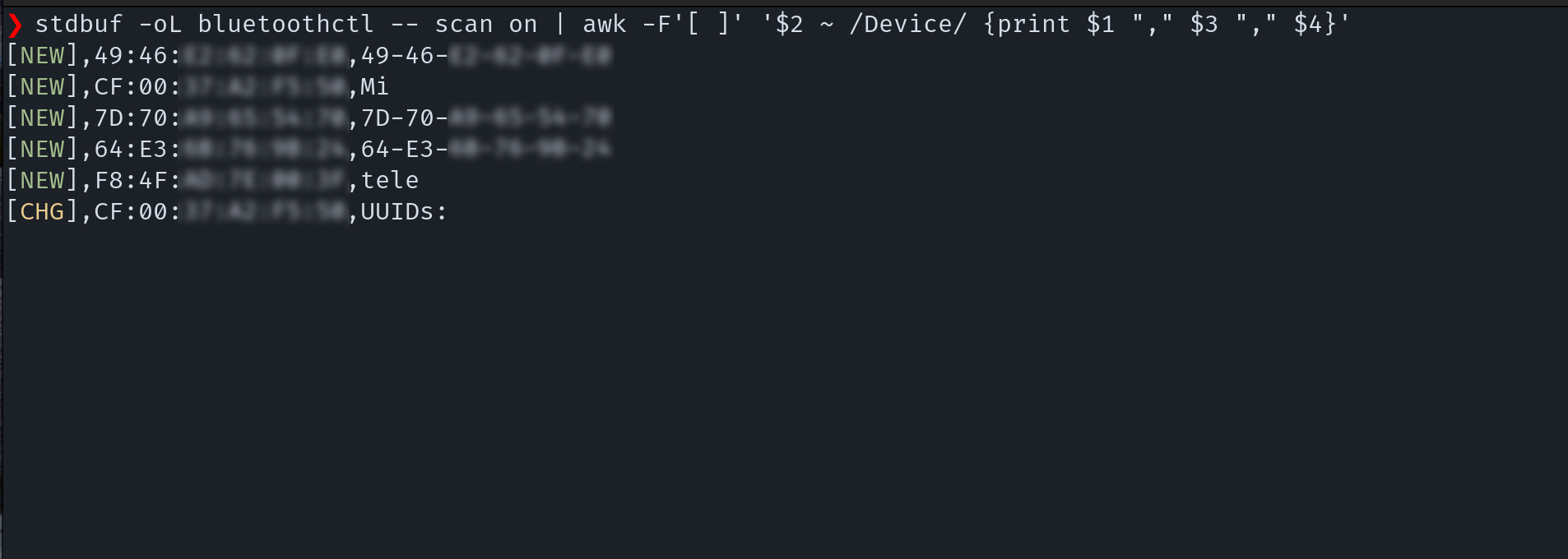

Knowing how to grab fields, I am now interested in grabbing only certain lines. You can set conditions for certain lines. I know that the lines I am interested in are the ones with “Device” in the second parameter. To put this in awk, it is expressed before the print command as follows:

stdbuf -oL bluetoothctl -- scan on \

| awk -F'[ ]' '$2 ~ /Device/ {print $1 "," $3 "," $4}'

You can even set several conditions, each with its own regex. In my case, the lines I’m interested in are the ones with a [NEW] or a [DEL], which is what determines when a device is found and when it is not detected. This, together with the “Device”, limits perfectly what I am trying to monitor. To set this, you put it with && and limiting conditions in brackets. As regexes are used, the single pipe (|) is used to say that any of these two values are valid, so it looks like this:

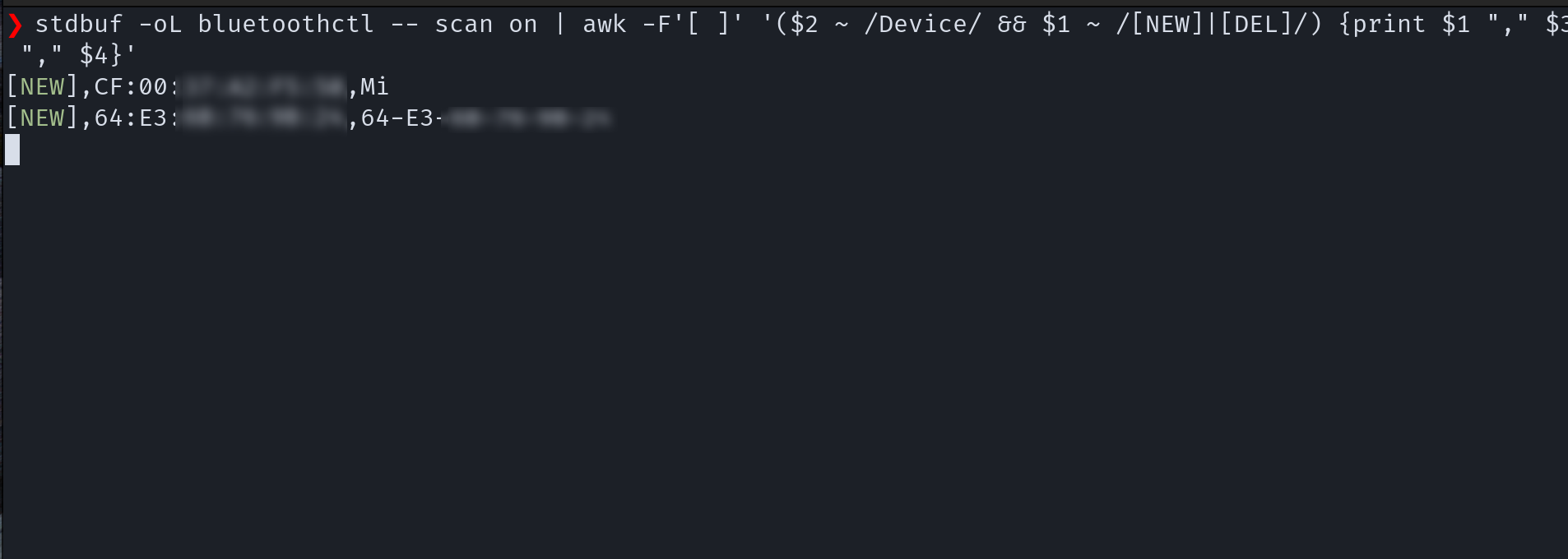

stdbuf -oL bluetoothctl -- scan on \

| awk -F'[ ]' '($2 ~ /Device/ && $1 ~ /[NEW]|[DEL]/) {print $1 "," $3 "," $4}'

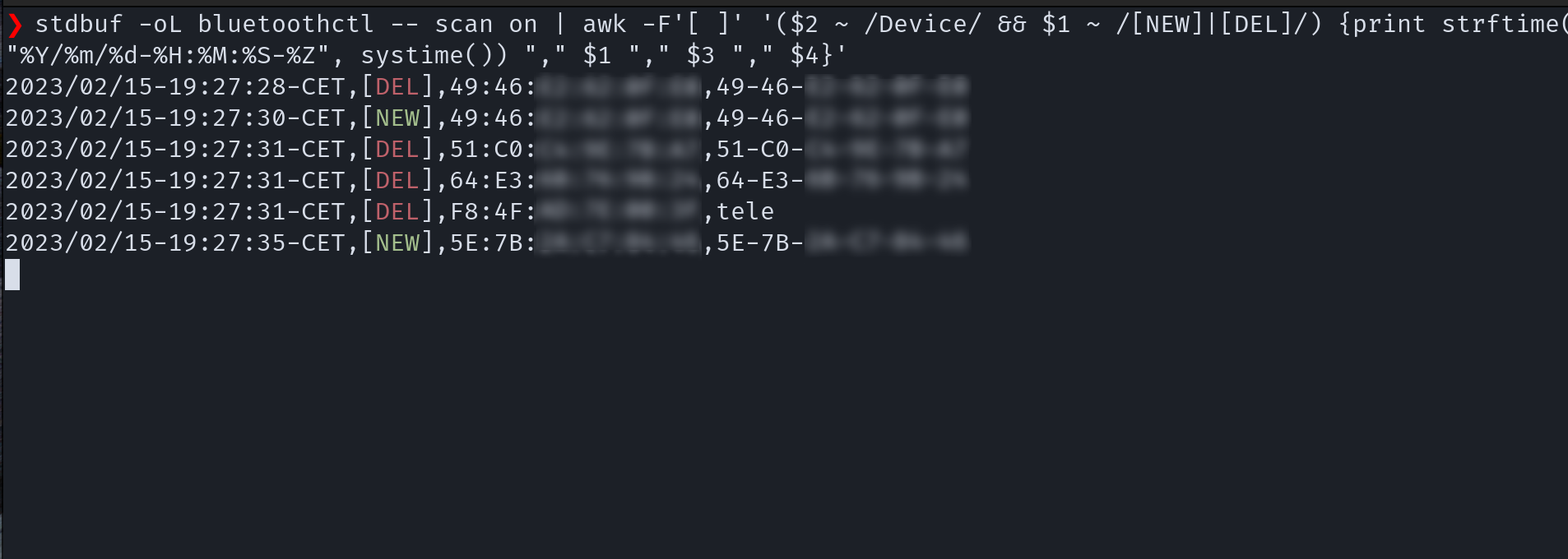

So far so good, but a log is useless if it doesn’t have timestamps. awk is so powerful that you can use some functions inside it (I don’t know if this is built-in of awk or not, but it is amazing). In this case, I add to my print a call to strftime() with the format I like, like this:

stdbuf -oL bluetoothctl -- scan on \

| awk -F'[ ]' '($2 ~ /Device/ && $1 ~ /[NEW]|[DEL]/) {print strftime("%Y/%m/%d-%H:%M:%S-%Z", systime()) "," $1 "," $3 "," $4}'

At this point I’m already amazed at what can be done with a single line and by putting commands together (I’ve saved so many lines of Python with this). Now, the last thing I need to do is to dump it to a file.

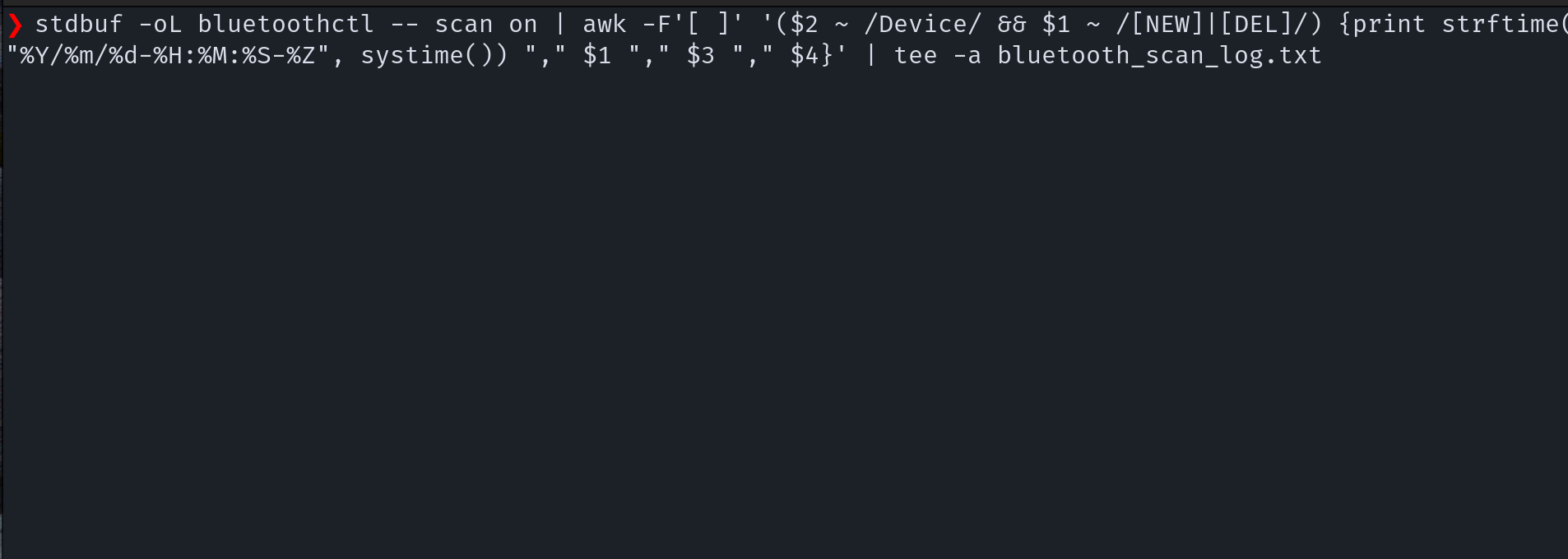

Something I was interested in was to dump it to a file but to see the output at the same time. For this tee is perfect. We pass the output from awk to tee with a pipe and we’re done:

stdbuf -oL bluetoothctl -- scan on \

| awk -F'[ ]' '($2 ~ /Device/ && $1 ~ /[NEW]|[DEL]/) {print strftime("%Y/%m/%d-%H:%M:%S-%Z", systime()) "," $1 "," $3 "," $4}' | tee -a bluetooth_scan_log.txt

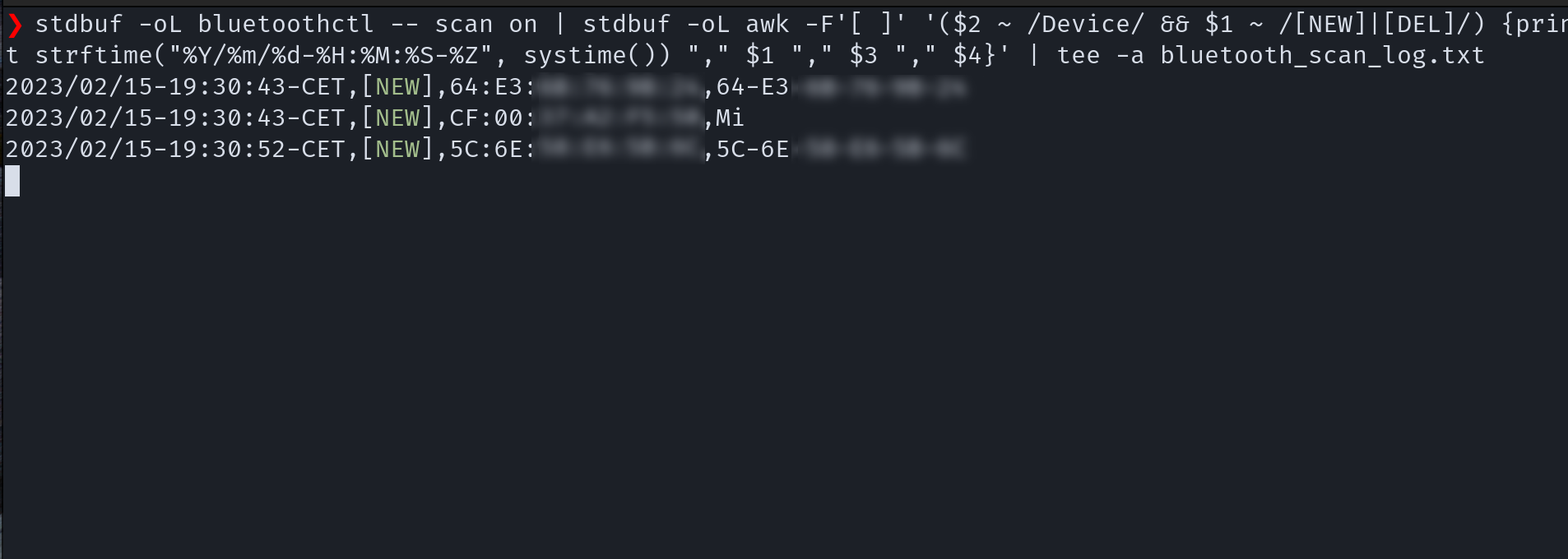

Shit. It doesn’t work. But wait, this sounds familiar. We have between awk and tee the same problem we had with bluetoothctl and awk, so we tried to solve it the same way and that’s it:

stdbuf -oL bluetoothctl -- scan on \

| stdbuf -oL awk -F'[ ]' '($2 ~ /Device/ && $1 ~ /[NEW]|[DEL]/) {print strftime("%Y/%m/%d-%H:%M:%S-%Z", systime()) "," $1 "," $3 "," $4}' \

| tee -a bluetooth_scan_log.txt

And that’s it. Now we have the whole “system” set up. Once done, I have seen that there are several details to correct, like maybe taking just those parameters is not a good idea because the fourth parameter can be cut with spaces, or maybe I am not interested in filtering so much information.

Anyway, that’s not the important thing. The essential thing is that, with a few commands, a bit of trial and error and our friends Google and man, you can set up a lot of things, without having to do scripts or anything. This has several advantages:

Use standard tools, which are available in most Linux distributions, which ensures that you can use it everywhere.

Less scripting. Don’t get me wrong, I love programming, but why do it if there are already solid and proven commands that allow you to do it. No need to reinvent the wheel, Keep It Simple, Stupid!

Be able to put it as an alias (or oneline function if quotes are too much trouble) in a

.bashrc(or.zshrcin my case). Running this by typing a single word makes you feel very powerful.

And that is all. I know, and I realised as I was doing it, that there are many ways to improve this. Some I’ve seen, some I haven’t even realised. My intention with this is just to show the beauty and the magic of using standard tools and the terminal, and how powerful these tools are to do a lot of things that, in the end, don’t need to be programmed.

Whenever you are going to do something like this, ask yourself if someone would be able to do this with a command. If the answer to that question is yes, look for it, and if you can’t find it, open the terminal.

Happy Hacking!